To Tape or Not To Tape: H-Taping

Taping can mean lots of things to lots of climbers. It can be a fashion statement, it can be a status symbol (“I climb therefore I tape”), or even a good luck charm (“I tape every time I climb because I sent that one time after I taped”). One truth about taping is that it is only supportive when it is necessary. Putting tape on like a weight belt to try the project and then removing it afterwards is definitely a thing. However, studies have shown that taping does not prevent injury. Even the taping that has been shown to aid in rehab of an acute injury does not prevent that injury from occurring. Anecdotally, when taping for the sake of taping becomes habitual (in my clinical experience), it can weaken the finger and leave it more prone to injury.

There is one type of taping that has been shown in the literature to be useful, and that is H-Taping. Isabelle Schoffl did a study published in 2007 that showed that H-Tape decreased the tendon-bone distance (TBD) in 12 rock climbers who had previously healed full pulley ruptures. Meaning, these athletes still showed increased TBD even after healing and returning to sport, but when H-Tape was applied, the TBD was decreased. H-Taping is used as a supportive orthotic to reduce the distance between the tendon and the bone, which is exceptionally useful when a pulley (A2 most specifically and A4 to a lesser degree) is strained or ruptured. H-Taping helps heal pulleys, but it does not prevent pulley injury. So at some point in time, we have to wean ourselves off the tape.

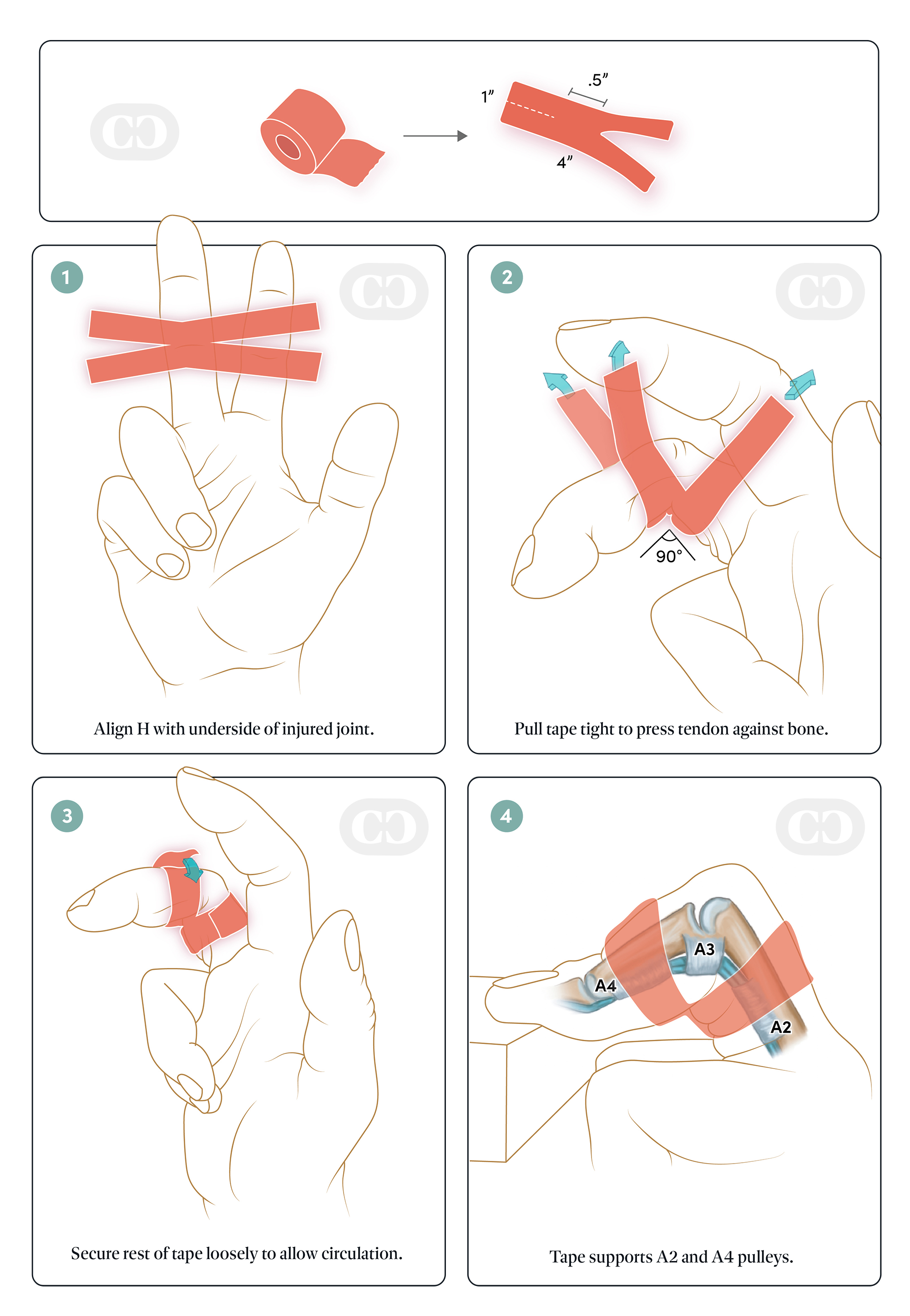

What is H-Taping?

A strip of tape is essentially cut into two strips but not completely, leaving a segment that remains intact right in the middle of the strip (forming what looks like an H). The application of this tape varies between no movement restriction and some movement restriction. In the study mentioned above, the tape was applied in such a way that it did not restrict any range of motion. But these were healed injuries, so asymptomatic, symptom free. The fingers weren’t injured but were measured retrospectively because they had known pulley ruptures in the past. These were healed fingers. When a pulley is injured, the (TBD) increases, reducing the ability of a finger to resist a load and to bend properly. If the H-portion of the tape is broad enough, it can be used to restrict motion. H-Taping helps support the tendon in lieu of a pulley so that you can still use your finger while it’s healing.

If you are H-Taping, a good rule to live by is that you shouldn’t pull with the finger any more bent than 80 degrees until the pulley is healed (which can take 2-6 weeks, depending). The tape can act both as a supportive, healing tool as well as a reminder of what actions you should be allowing the finger to make. In the study mentioned above, an unintended outcome of taping the healed injuries was that the climbers not only felt stronger, but also their strength in a full crimp position was measurably stronger.

There is more to this discussion than just healing pulley injuries. I am not promoting the use of H-Tape to just climb through your pulley injury. I have many more thoughts on this subject especially as it relates to soft tissue adaptation in climbers, measuring TBD, and healing pulleys prior to load. So stay tuned!

CCDPT